Ex Libris #16 A Tale of Two Books

I recently put out a kind of community-all-points call to friends and acquaintances for e-books of all types, and thanks to the generosity of the book community, I was duly inundated.

I recently put out a kind of community-all-points call to friends and acquaintances for e-books of all types, and thanks to the generosity of the book community, I was duly inundated.

Titles of all types and descriptions started flooding in, formatted for epub or mobi or pdf of what-have-you, and all that was left for me to do was download them all and parcel them out to my various devices, since a) some of them read some formats better than others, and b) it buys a bit of mental relief to have redundant libraries on many different devices, just in case one device or platform abruptly gives up the ghost.

The sheer abundance of the titles that came pouring in sparked some odd and sometimes contrary impulses. For many decades of buying printed books, my frame of mind was almost entirely exclusionary: I knew what I liked, I knew what seemed interesting, and I was open to new reading experiences … but I was surrounded with millions and millions of books of all descriptions, all wanting my attention and, more importantly, all demanding space in my already-crowded bookish space.

Already here in the place, there are bookcases climbing the walls everywhere, books stacked neatly everywhere, books on ‘waiting’ shelves in hopes of meriting a spot on the more-or-less-permanent shelves, and books stacked neatly on the floor waiting to be sorted for resale or donation … books everywhere, in other words.

This naturally has always made me wary about taking in new books, but when it comes to e-books, there’s no need for such wariness; as long as I’ve got enough electronic storage, I can download every single one of these titles so generously being offered by friends. A hundred of them – a thousand of them – two thousand of them – it doesn’t increase the size or weight of my iPad at all, and who knows but that I might end up liking e-books I’d have turned away reflexively if trying them meant finding shelf-space for their printed versions?

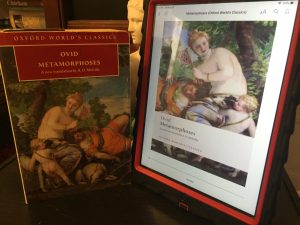

I was thinking of all this more pointedly than usual lately, because one of those friends sent me the e-book of the translation A. D. Melville made of Ovid’s Metamorphoses for the Oxford World’s Classics line back in 1986.

I’ve had the paperback well over 30 years. It’s moved with me from apartment to apartment, it’s grown creased and scuffed, and it, like all my other printed books, appreciates regular dusting. Since the Metamorphoses is my single favorite book, I’ve read this Melville translation a few times, always with a pencil in hand, always learning something new. “English has one great advantage over Latin,” Melville writes in his Translator’s Note “- its vocabulary is so much larger. A translator may often have three or four words where Ovid has only one; and these three or four will all be subtly different. Conversely he can often express in one apt word a meaning for which Ovid needs several.” It’s fascinating to watch that ideology play out over the course of Ovid’s long and enchanting poem.

Given that, you might think I’d have no interest in downloading the e-book. You might think I’d see the offer and think, “No, I already have that book.”

But I don’t already have that book right here. I don’t already have that book on the subway, or trapped in a long line at the post office, or even when struck by the urge to read a particular story in the Melville Metamorphoses while laying in bed with a bossy little Schnauzer sleeping peacefully. In all of those circumstances, my iPhone is within easy reach.

The e-book never needs dusting. It never needs packing or unpacking. It never even needs a pencil in hand, since the e-book file allows for a near-infinite amount of note-taking in a window that pops up specifically for that purpose, without any need to find space in miserly margins. The e-book automatically reminds me of the place where I stopped reading; it can be repositioned on any electronic ‘shelf’ I select; it’s totally unappetizing to aphids and silverfish; it will not fade in the sun or mold over in the summer humidity.

Ah, I hear Old School purists object, but your precious e-book requires that your reading device be charged! Which in turn requires that you have access to a steady supply of electricity! It’ll do you precious little good if you’re out camping for a week! To which I always ask: when’s the last time you went camping for a solid week? And when was the time before that? Who contours their reading with an eye to once-in-a-decade exceptions to the rule?

Ah, those determined Old Schoolers persist, but if you’re reading The Metamorphoses you won’t need us to point out the obvious: things change! What happens in ten years when the file-format of all those e-books is no longer readable by new devices? What happens if one of those devices suddenly crashes, completely dead, taking all your books with it? The only reason you’re able to read Ovid today is because those kinds of things don’t happen with printed books – they worked just fine, requiring only light enough to see, two thousand years ago, and they work just fine today, and as long as anybody can read or translate human languages, they’ll work just fine two thousand years from now.

To which I always ask: are you planning on being around in two thousand years? Most e-books are in very open, very adaptable formats that virtually any operating system can read, and most of those operating systems are pretty good at converting the stuff they can’t read into stuff they can. The dawn of home computing might be one thing, but pretty much all technology created since the advent of ‘smart’ tech is very consciously retentive; it very seldom leaves things behind.

Of course, the Old Schoolers are right about one thing: an electronic device can just up and brick on you – fine one minute, a useless, inert block of plastic the next, reasons unknown. And equally true, that never happens to a printed book. Absent bugs and fires and water damage, a printed book is always there, eager to be enjoyed.

But my e-book library is equally eager, and it’s now sprawled over three devices, one of which is almost always within easy reach.

As for that Melville Metamorphoses, I’ll be keeping both.

Steve Donoghue is a book reviewer and editor living in Boston (with his inquisitive little Schnauzer Frieda). His work has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and Kirkus Reviews, and he writes regularly for the Christian Science Monitor, the National, and the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette. He is a proud Weathersfield Proctor Library patron.